08 January 2019

roadmap

belgium / EU

FDI in Europe – what to expect?

Disclaimer: This article had been prepared prior the interinstutional negotiations ("trilogues") took place.

I. Introduction

In September 2017, the European Commission ("Commission") tabled a proposal for a new European framework to screen foreign direct investments ("FDI") into the European Union. The proposal is the EU's response to the emerging trend of screening foreign investments. In his State of the Union speech, the president of the Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, called for greater protection of the EU's strategic interests, while stressing that FDI should be subject to transparent scrutiny. With this initiative, the EU is following a number of jurisdictions that have already implemented FDI screening mechanisms, that are increasingly employed to scrutinise investments. These include major economies such as Australia, Canada, China, Germany, India, Japan, Russia and the USA.

Whilst the EU wishes to retain an open approach towards FDI, which are widely regarded to contribute to economic growth and welfare, recent developments have pointed towards the threat to security or public order posed by certain FDI. These concerns were fuelled by the suspicion that some FDI seem to be (foreign) state-orchestrated attempts to tap into critical European technologies, infrastructure, inputs or sensitive information in the pursuit of a national industrial/geopolitical agenda. This, understandably, puts FDI in sensitive areas into the spotlight. By the same token, the (mostly) unrestricted access to the EU markets was not seen to be reciprocated with equally free access to foreign markets for EU companies.

The debate around FDI gained further traction when the flow of Chinese investments into the EU peaked in 2016, while investments from the EU to China continued to decrease. This led the Italian, French and German ministers in a concerted action to voice their concerns in a letter to the EU Commissioner for Trade, Cecilia Malmström, which set things in motion in the EU.

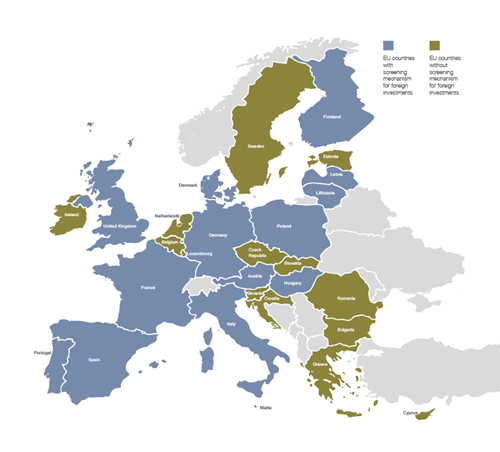

The inflow of FDI has also led several Member States, such as Germany, France, Poland, Finland and Italy, to step up their FDI screening mechanisms. For instance, the acquisition of the German industrial robot builder Kuka by China's Midea Group is widely regarded as having triggered the tightening of the German FDI screening rules. Since then, Germany has been sending foreign investors a clear message that national security takes priority over economic interests. Indeed, in August 2018, Germany banned the acquisition of Leifeld Metal Spinning, a company producing machines and tools used in the nuclear, aerospace and automotive industries. At present, there is no uniform let alone harmonised FDI screening mechanism at the EU level. Thirteen Member States have national screening mechanisms: Austria, Denmark, Germany, Finland, France, Latvia, Lithuania, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain, the United Kingdom and Hungary, which adopted its FDI screening mechanism only in October 2018.

These screening mechanisms diverge in terms of grounds for screening, deadlines, scope of application, qualitative criteria and quantitative thresholds. The absence of a comprehensive FDI screening mechanism and of an institutionalized cooperation platform among the Member States prevents effective monitoring of FDI flows into the EU.

What is more, the regulatory / enforcement gap is seen as potentially having adverse implications on the security and interests of the Member States as well as the EU as a whole. In addition, the divergence of applicable FDI rules creates uncertainty for foreign investors, who are exposed to various screening regimes across the EU. The now proposed legislation, which comes in the form of a draft regulation (the "Regulation") aims to close this gap.

II. Proposed regulation

The Regulation does not purport to create a harmonised EU FDI screening mechanism, nor does it seek to bestow the Commission with enforcement powers in the area of FDI. By the same token, it does not require Member States to adopt or maintain national FDI screening mechanisms, but aims to span a common framework across the EU that tackles the above shortcomings by enhancing cooperation and information exchange between the Member States and the Commission, setting out common standards and factors to be considered during the screening, while allowing Member States to take account of their individual situation and national circumstances.

(i) Scope of the Regulation

The Regulation covers any kind of investment by a non-EU investor who aims to establish or maintain lasting and direct links with the investee in order to carry on an economic activity in the Member State, including investments which enable effective participation in the management or control of a company carrying out an economic activity. Unlike the EU Merger Regulation, it does not set out quantitative thresholds that would trigger the FDI screening.

(ii) Member State screening mechanism

Under the Regulation, Member States may maintain, amend or adopt mechanisms to screen FDI on the grounds of security or public order, provided that the conditions and the terms set out therein are observed. The Regulation provides uniform standards for all national screening mechanisms. As such, the screening mechanisms must:

- be transparent, particularly with respect to the grounds for screening, the applicable procedural rules and the circumstances triggering the screening;

- not discriminate between third countries;

- have a clear timeframe for issuing the screening decisions (taking into account the time limitation for the Member States and the Commission to submit their comments / opinion);

- protect confidential information; and

- allow the parties to seek judicial redress against screening decisions.

(iii) European Commission screening procedure

If the Commission believes an FDI is likely to affect projects or programmes of Union interest due to reasons of public order or security, it may issue an opinion addressed to the Member State where the FDI is planned or has already been completed. Such programmes of Union interest should include those projects and programmes which involve a substantial amount or a significant share of EU funding, or which are covered by Union legislation regarding critical infrastructure, technologies or inputs. The Regulation is accompanied by an Annex listing projects and programmes of Union interest. The opinion must be issued within a reasonable period of time, but not later than 25 working days from the receipt of the information requested by the Commission or from the day the Commission was notified of the FDI in question. The Commission's opinion should be further communicated to all other Member States, which can follow up with their comments.

The Member State in whose territory the FDI is planned should take utmost account of the Commission's opinion and provide the Commission with an explanation should it decide not to follow the Commission's recommendations.

(iv) Cooperation mechanism

The draft Regulation lays down grounds for allowing the Member States and the Commission to cooperate and assist each other when FDI is likely to affect their security or public order.

To this end, Member States should inform the Commission as well as the other Member States of any FDI that are subject to screening under their national screening mechanisms within five working days from its commencement. Where another Member State considers that the FDI under the screening is likely to affect its security or public order, it may provide comments to the Member State concerned. Similarly, the Commission can issue an opinion. The comments/opinion should be addressed to the Member State no later than 25 working days following the commencement of the screening or the receipt of the requested information.

(v) Non-exhaustive list of factors for the screening process

The Regulation sets out a non-exhaustive list of factors which the Member States / Commission should take into consideration during the screening process. They should pay particular attention to the potential effects on:

- critical infrastructure – including energy, transport communications, data storage, space or financial infrastructure, as well as sensitive facilities;

- critical technologies – including artificial intelligence, robotics, semiconductors, technologies with potential dual use applications, cybersecurity, space and nuclear technology;

- the security of supply of critical inputs; or

- access to sensitive information or the ability to control sensitive information.

As part of the assessment, the Member States and the Commission may also consider whether the foreign investor is directly or indirectly controlled by the government of a third country, including through significant funding.

(vi) Reporting obligation

With a view to maximise the transparency of FDI monitoring within the EU, the Regulation obliges the Member States to notify the Commission of their screening mechanisms or amendments, and to submit annual reports on the application of their screening mechanisms. Member States which do not have any screening mechanisms in place must nevertheless report all FDI that occurred in their territory.

III. Outlook

The proposed Regulation is currently in a phase of interinstitutional consultations among the Parliament, the Council and the Commission (trilogue meetings), after which the final proposal will be submitted to the plenary of the European Parliament and the Council for the first reading. It was initially envisaged that the Regulation should be adopted by the end of this parliamentary term in May 2019. However, bearing in mind the lengthy nature of EU legislative procedure, this might be delayed into the second half of 2019.

It is already clear that for the proponents of a centralised EU vetting system, the legislation will not meet the hopes that were put into the initiative. Yet, it remains to be seen how the FDI screening will be implemented in practice and what factual weight the Commission will have under the framework which the Regulation aims to set in place. In any event, the legislation signifies a first move in framework for FDI screening.

This article was co-authored by Monica Svikova.

-----

This article was up to date as at the date of going to publishing on 10 December 2018.

Volker

Weiss

Partner

belgium / EU